Public Affairs Online:THE TAX REFORM SERIES

Introduction

From the Public Affairs Online platform of CMC Connect come this analysis series, developed to contribute informed, evidence-based perspectives to Nigeria’s evolving tax reform discourse. The series is published against a backdrop of mounting fiscal pressure, rising costs of living, heightened public concern, and growing scrutiny of how tax policies affect every day Nigerians.

Rather than focusing narrowly on revenue mobilisation, the series interrogates the broader policy questions surrounding the new tax reform. These include issues of fairness, sustainability, economic impact, and public trust. Each installment builds on the last, combining fiscal context with lived economic realities to support balanced, credible, and constructive public discourse.

We begin by examining why tax reform has returned to the centre of Nigeria’s national policy debate.

Why Tax Reform Matters Now!

Nigeria’s tax system has long been criticized for being fragmented, complex, and difficult to navigate. Multiple laws govern personal income tax, corporate tax, capital gains tax, value added tax, and stamp duties, often resulting in overlapping obligations and administrative inefficiencies.

In response, the Federal Government introduced a comprehensive Tax Reform Bill, comprising four new Acts: the Nigeria Tax Act, the Nigeria Tax Administration Act, the Nigeria Revenue Service Establishment Act, and the Joint Revenue Board Establishment Act.

Signed into law on June 26, 2025, by President Bola Tinubu, with a commencement date of January 1, 2026, the reforms aim to modernize tax administration, close loopholes, reduce complexity, and improve transparency across all tiers of government.

For businesses and households alike, multiple taxation has long been a central concern. Federal, state, and local governments frequently impose overlapping taxes and levies on the same economic activities. In practice, much of this burden is passed on to final consumers through higher prices. This dynamic has contributed to sustained calls for harmonization of Nigeria’s tax framework, particularly as operating costs rise and purchasing power weakens.

Tax reform has returned to the policy agenda not by coincidence, but by necessity. Declining oil revenues, persistent fiscal deficits, and rising expenditure demands have converged with growing public expectations. The result is an urgent reckoning with how government raises revenue, who bears the burden, and whether the current system can sustainably fund national priorities?

At the core of the challenge is a structural mismatch between public obligations and public income. Nigeria’s expenditure needs continue to expand, driven by infrastructure gaps, security pressures, social sector demands, and the costs associated with a rapidly growing population. Public revenue, however, has struggled to keep pace, leaving government increasingly reliant on borrowing to close recurring gaps.

The Tinubu administration has framed tax reform as a response to these pressures, emphasizing base expansion and improved compliance rather than higher tax rates. According to the Chairman of the Presidential Committee on Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms, Mr Taiwo Oyedele, “The economy is struggling because there is an excess tax burden. So, let’s take that burden away so people can breathe.” He has argued that harmonization will reduce the number of taxes and levies faced by businesses, improve competitiveness, and support growth driven by economic expansion rather than aggressive taxation.

Nigeria’s tax to GDP ratio, estimated at around 10 percent, remains among the lowest in Africa. A relatively small segment of individuals and businesses accounts for most direct tax revenue, while a large informal economic actors operates outside the formal tax net. As a result, indirect taxes have become an increasingly important source of government income.

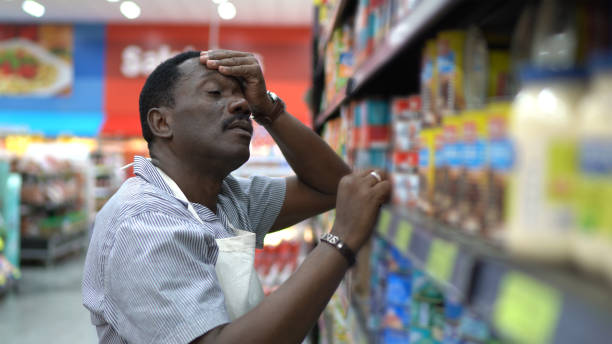

While easier to administer, consumption-based taxes carry clear distributional consequences. Lower- and middle-income households typically spend a larger share of their income on consumption, meaning they feel the impact of such taxes more acutely. Over time, this can erode disposable income, amplify inflationary pressures, and weaken confidence in the perceived fairness of the fiscal system.

Are Nigerians Overburdened with Taxes?

This raises a central question that underpins current public debate: are Nigerians under taxed on paper but overburdened in practice? While macro indicators suggest low tax effort relative to GDP, lived experience tells a more complex story shaped by rising prices, multiple levies, and limited access to public services.

Tax reform, therefore, cannot be assessed solely through the lens of revenue mobilization. It is also about sustainability and legitimacy. Rising debt service costs, persistent budget deficits, and limited fiscal buffers have narrowed policy space, making predictable and resilient revenue structures more important than short term fixes.

Public trust sits at the heart of this challenge. Tax systems function best when citizens believe the burden is shared equitably and that public resources are translated into visible outcomes. In Nigeria, skepticism has been shaped by longstanding governance concerns and the gap between taxes paid and services delivered. Any reforms that fail to address this trust deficit risks limited traction, regardless of its technical strengths.

Seen in this context, tax reform is not merely a fiscal exercise. It is a governance question that speaks to obligation, capacity, and fairness. As implementation unfolds, this series examines not only what is changing, but why it matters, who it affects, and how design choices shape economic outcomes beyond revenue figures. Subsequent parts will draw on comparative analysis and survey insights to ground these discussions in evidence and public experience.

Watch Out for Part 2